[Download for Mac] [GitHub/Code]

Ever since I’ve been a little child playing with sticks, hitting leaves and listening to the rustling of the wind in the wild, deep forests during those dry hot summer days, I have been dreaming of creating soundscapes with massively large and dependable computing equipment. The kind of equipment that is built to look incredibly badly designed so as to show off its functionality. Swamped with vacuum tubes, standing quietly in the corner humming to itself and collecting dust. This equipment has ceased in its endeavours to collect dust as it has been replaced by similar badly designed equipment running with stupefyingly fast processors that produce more heat than light.

My desire to create the perfect soundscape to accompany my day dreams while working in an office never dissipated and I always have kept that dream alive. It took many iterations, each sounding quite similar to a rusty nail being polished, to finally find a piece of software capable of fulfilling my dream. This dream began with a Unix shell-script and some C code, continued in the exploration of unexplored wild-west like frontier of the internet, finally ending the recesses of a collider built into the side of a virtualised supertanker.

Providing the emulations of those long lost and forgotten vacuum tube monsters, support for the superb midi protocol and an incredibly complicated why of programming, SuperCollider has become the tool for my personal realisation and fulfilment of a long and almost given up dream of creating soundscapes to accompany my literary exploration of the worst possible ways to explain this project.

Long windedness of texts is an unfortunate natural consequence of the complexity and ever alternating nature of the soundscapes that happen to be generated using the software I created to fulfil my life-long dream of creating soundscapes. The ever undulating movement of samples that, individually, provide little entertainment, incredibly when combined with other samples of little talent, however, produce a universal world of beauty and ambience. Adding further colour into the mix, are simple and effective effects applied directly to the samples, to provide an overall colourful kaleidoscope generated by the minor and extremely simple pressings of buttons and dialling of knobs.

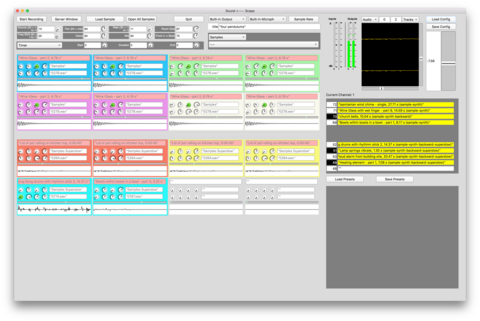

The graphical user interface provides an intuitive and extremely usable collection of dials, knobs and buttons, occasional drop down menus round-off that usability. Complexity has been done away with to be replaced by confusion and doubt. Incredibly it provides a brilliant and enlightening user experience if you happen to own or have borrowed or even stolen an Arturia Minilab Mk II Midi Keyboard that most probably, by pure coincidence and good fortune, has the same correct key mappings as assumed by the software. A copy of these mapping can be obtained here for the keys towards you and a second mapping for the keys away from you. I have found that having the rows of dials towards me, to be easier to work with than reaching over the keys to access the dials.

Basis of any good soundscape application is the quality of the samples, all recorded using a cheap or rather affordable dictator device - Philips DVT4000 Voice Tracer. Which surprisingly does, with a bit of practice and button pressing, providing sufficiently good samples that seem to have little detrimental effect on the overall quality of the completed soundscape. Unfortunately not all samples are immediately loopable (or to use the more technical term: loopy) and therefore require some tender loving care from Audacity (be careful of the spyware version).

This completes the helpful collection of equipment that fulfils my life long dream and, surprisingly, there are no vacuum tubes involved. Unfortunately my MacBook seems to have taken personal offence to the omission in this equipment listing and decided to freeze on me. Recovery is swift, on goes this text. Thankfully Bose equipment does not seem to display a similar disrespect for owners and their forgetfulness. There is a set of Bose noise cancelling bluetooth headphones on my desk as I write these words, which were - the headphones not the words - previously located on my head, producing sound waves in the vicinity of my ears which allowed me to personally enjoy a collection of soundscapes.

Of course the most important non-physical part of this project are the samples. All the samples I use have been recorded by me somewhere at a location where I was previously engaged in some activity. Sounds range from birdsong, to lawnmowers, to thunder, to rain, to cars, … everything where I remember to record it has been recorded.

Interestingly, having recorded the samples myself, I have imagery associated with each sample, so when I listen to the soundscapes I have a complete set of images in my head. But I have completely different pictures in my head, for example, when I listen to the sample with chickens, I have an image of me standing at a fence in the middle of field of stinging nettle while the chickens go about their busy. It is an exercise for the reader to reflect on their own images of chickens.

Sounds from the Scape composer software

My initial aim was to create a random music composer, ideally to provide some funky techno beats. I would provide the samples and the machine would provide the soul. However, needless to say, since machines are soulless, that failed.

The initial attempt consisted of a shell script and wavplay which did a good job of creating random soundscapes and not much else. Because of the nature of the beast: randomly introducing samples and randomly fading them out again does not provide for consist listening pleasure, especially if the samples contain beats.

Sometime later, I ran across SuperCollider and began experimenting around with the GUI elements provided. I initially designed the GUI to be used with a mouse but discovered that turning virtual dials with a mouse was no fun. That discovery led to the invention of the randomisation button, that then got the software to do the turning for me.

I still got no satisfaction and eventually had a eureka moment and connected my AKAI MPKmini MKII Midi keyboard to the software. SuperCollider has a super simple Midi interface and working with the midi keyboard made everything a lot simpler, bring a whole universe of new dials and knobs to the software.

The project took a giant leap forward with the purchase of an Arturia Minilab mkII keyboard. I was looking for something with more dials and more importantly dials that rotated through 360 degrees, i.e., no physical stop. This is important since all virtual dials in the software are positioned differently. So if the physical dial reaches a stop, changing the virtual dial in that direction was impossible. The Arturia has sixteen dials of pure turning pleasure and their software allowed me to remap these to do whether I wanted.

I constantly adjust the software to my needs and purposes. That is the great freedom I have in coding my own software. Of course, I could use an off-the-shelf loop machine, but having no musical talent, there is no real point in doing that - in addition to the financial cost. One feature I recently added was recording the turning of the dials. I noticed one day that I only had two hands but sixteen physical and sixty-four virtual dials, doing the numbers I realised I needed something to turn dials for me.

This lead to the invention of the pendulum feature which, provided with start and end points and a time period, will smoothly pendulate the dial between the end and start points over the given time period. Alternatively I can record my dialling of a given knob over some time and the software will faithfully rinse and repeat that dialling over the same time period.

Purpose

So what is the purpose of all of this? For me, soundscapes are blankets around my ears that block out the street noise emanating from my window, they provide a constant but ever slightly changing sound-carpet that under lies my creative process. They distract part of my conscious, making my conscious partly focus on something that it cannot possible understand. My conscious is distracted in attempts to recognise patterns in these random soundscapes. That allows my subconscious to sneak in and write these words.

The soundscapes are not randomly generated, I spend a good deal of time finding the right combination of oscillators, samples, effects and pendulums to get something that provides the level of distraction necessary for the creative pursuit that I am actually trying to follow up on.

To put it a little more explicitly, the soundscapes I produce have the single purpose of distracting my conscious, providing me with more focus to complete other creative pursuits. I would also describe it as providing a kind of sucking device that sucks away any excessive and unnecessary thoughts. Or better said: the soundscapes are the light attracting the mosquito-like thoughts that fly around my head. Mosquito-like because these thoughts suck, out of me, all my focus and mental energy.

As such, I have found that soundscapes are best utilised by using good headphones, not in-ears. For me, thats when these soundscapes provide the best protection against procrastination.

Hence these soundscapes are not designed to be everyones musical taste, they might not fulfil the purposes you might have in mind however they sit very well in my musical world view. This author used to be a big fan of subradar.no before they shut down.

Support

If you have made this far, thanks for reading. If you want to support the project or purchase a soundscape, checkout Soundcloud for samples and Gumroad for purchasing. Donations are also very much acceptable.

Postscriptum

This passage in Douglas Adams’ Dirk Gently Holistic Detective Agency also talks about music and the relevance to the conscious. Ironically I am quoting the book as it quotes a fictive magazine, so this then becomes a double-quote (pun intended):

We know, however, that the mind is capable of understanding these matters in all their complexity and in all their simplicity. A ball flying through the air is responding to the force and direction with which it was thrown, the action of gravity, the friction of the air which it must expend its energy on overcoming, the turbulence of the air around its surface, and the rate and direction of the ball’s spin.

And yet, someone who might have difficulty consciously trying to work out what 3 x 4 x 5 comes to would have no trouble in doing differential calculus and a whole host of related calculations so astoundingly fast that they can actually catch a flying ball. People who call this ‘instinct’ are merely giving the phenomenon a name, not explaining anything.

I think that the closest that human beings come to expressing our understanding of these natural complexities is in music. It is the most abstract of the arts - it has no meaning or purpose other than to be itself.

Every single aspect of a piece of music can be represented by numbers. From the organisation of movements in a whole symphony, down through the patterns of pitch and rhythm that make up the melodies and harmonies, the dynamics that shape the performance, all the way down to the timbres of the notes themselves, their harmonics, the way they change over time, in short, all the elements of a noise that distinguish between the sound of one person piping on a piccolo and another one thumping a drum - all of these things can be expressed by patterns and hierarchies of numbers.

And in my experience the more internal relationships there are between the patterns of numbers at different levels of the hierarchy, however complex and subtle those relationships may be, the more satisfying and, well, whole, the music will seem to be.

In fact the more subtle and complex those relationships, and the further they are beyond the grasp of the conscious mind, the more the instinctive part of your mind - by which I mean that part of your mind that can do differential calculus so astoundingly fast that it will put your hand in the right place to catch a flying ball - the more that part of your brain revels in it.

Music of any complexity (and even ‘Three Blind Mice’ is complex in its way by the time someone has actually performed it on an instrument with its own individual timbre and articulation) passes beyond your conscious mind into the arms of your own private mathematical genius who dwells in your unconscious responding to all the inner complexities and relationships and proportions that we think we know nothing about.

Some people object to such a view of music, saying that if you reduce music to mathematics, where does the emotion come into it? I would say that it’s never been out of it.

The things by which our emotions can be moved - the shape of a flower or a Grecian urn, the way a baby grows, the way the wind brushes across your face, the way clouds move, their shapes, the way light dances on the water, or daffodils flutter in the breeze, the way in which the person you love moves their head, the way their hair follows that movement, the curve described by the dying fall of the last chord of a piece of music - all these things can be described by the complex flow of numbers.

That’s not a reduction of it, that’s the beauty of it.

This quote comes from Chapter 19 and is included in the fictive magazine Fathom and was written by Richard MacDuff.

Two things stand out for me in this quote, one is the description of the unconscious as being that part of the brain that is doing the complex calculus to catch the ball. Exactly that fascinates me about the subconscious (or unconscious, for me same-same), that it has all these abilities to coordinate muscles, perform complex calculations and all sorts of other abilities leaving our conscious to idle around and push off commands to the unconscious.

For me, just as we can say to to our unconscious I want to drink a glass of water and the unconscious will coordinate all the muscles to make that happen, so we can also give the subconscious questions that it will eventually resolve, for example: what is the question for answer 42? The only caveat is that we don’t know how long the unconscious will take to resolve those questions, or if it ever will.

An example of this is forgetting someones’ name. You suddenly find yourself thinking about someone and then you notice you have forgotten their name. No matter how long you think about, you just can’t remember the name. So you leave it to your unconscious and distract your conscious with something else. Eventually the name will pop into your head. Was that some sort of channeling the afterlife or was it simply your unconscious coming up with the solution to the question: what is the name of so-and-so?

Secondly I found the description of the complexity of music speaking directly to the unconscious completely contra to what I have been describing, my attention is to distract the conscious, what MacDuff/Douglas is saying that musical complexity actually entertains the unconscious. Whatever is the case, the affect is the same: my mind is clear and I can focus on whatever task I intend to perform.